What is Micro Bacteria?

Any part of the human body that is open to the outside world it available for the colonisation of bacteria. While this blog has covered bacteria in the and the throat, one area I've neglected to cover is the bacteria that get into the lungs. As the company I currently work for is involved in respiratory research I was rather excited to find a PLoS One paper that looked at how the population of lung bacteria changes in respiratory disease.

Any part of the human body that is open to the outside world it available for the colonisation of bacteria. While this blog has covered bacteria in the and the throat, one area I've neglected to cover is the bacteria that get into the lungs. As the company I currently work for is involved in respiratory research I was rather excited to find a PLoS One paper that looked at how the population of lung bacteria changes in respiratory disease.

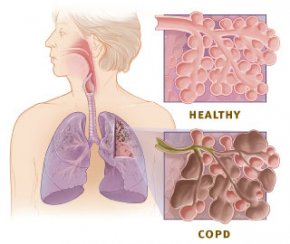

The respiratory disease in question is COPD, which stands for chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. It's caused primarily by smoke getting into the lungs, from tobacco or industrial processes, and leads to narrowed airways and overproduction of mucus. It's not really curable, although many medications exist to help people live with it, and to slow down the progression of the disease.

In order to explore which bacteria were present in healthy smokers, COPD patients, and people who had never smoked, researchers used massively parallel pyrosequencing. This technique allows the bacteria to be identified by their DNA without the need for producing bacterial cultures, so even 'unculturable' bacteria can be identified.

In the smokers, never-smoked, and patients with mild COPD a far wider range of bacterial diversity was found than in patients with severe COPD who tended to have a much smaller number of different bacterial species. There were no specific bacterial species common for each group, the major difference appeared to be in diversity. The most commonly found bacteria in the healthy subjects included Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella and Fusobacterium which the researchers suggested may make up a core lung microbiome.

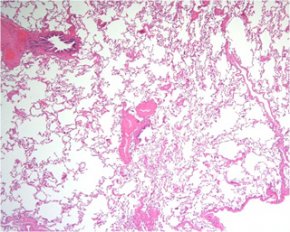

As a secondary analysis, the researchers also looked at bacterial populations in very specific areas of the lung, and found that there was no homology of bacterial species throughout the whole lung. In some cases one small microenvironment in the lung could be exclusively populated by one form of bacteria. Samples from different places in the lungs could therefore result in a very different view of the bacterial microflora in the lungs.

As a secondary analysis, the researchers also looked at bacterial populations in very specific areas of the lung, and found that there was no homology of bacterial species throughout the whole lung. In some cases one small microenvironment in the lung could be exclusively populated by one form of bacteria. Samples from different places in the lungs could therefore result in a very different view of the bacterial microflora in the lungs.

Although this research is fascinating, it is important to note that despite differences seen the microflora cannot be used as a diagnostic for COPD as there were no exclusive differences seen in this small sample size between diseased and healthy lung flora. The small patches of different microflora may suggest areas that are more prone to developing COPD and other respiratory diseases, in the same way that patches of different skin bacterial flora can be more prone to dermatitis and skin diseases.

Reference: Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, et al. (2011) Analysis of the Lung Microbiome in the “Healthy” Smoker and in COPD. PLoS ONE 6(2): e16384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016384