Cell Structure, Function

WHY did nature evolve cellular structures?

WHY did nature evolve cellular structures?

In, I laid out a structural classification of cellular structures in nature, proposing that they fall into 6 categories. I argued that it is not always apparent to a designer what the best unit cell choice for a given application is. While most mechanical engineers have a feel for what structure to use for high stiffness or energy absorption, we cannot easily address multi-objective problems or apply these to complex geometries with spatially varying requirements (and therefore locally optimum cellular designs). However, nature is full of examples where cellular structures possess multi-objective functionality: bone is one such well-known example. To be able to assign structure to a specific function requires us to connect the two, and to do that, we must identify all the functions in play. In this post, I attempt to do just that and develop a classification of the functions of cellular structures.

Any discussion of structure in nature has to contend with a range of drivers and constraints that are typically not part of an engineer’s concern. In my discussions with biologists (including my biochemist wife), I quickly run into justified skepticism about whether generalized models associating structure and function can address the diversity and nuance in nature – and I (tend to) agree. However, my attempt here is not to be biologically accurate – it is merely to construct something that is useful and relevant enough for an engineer to use in design. But we must begin with a few caveats to ensure our assessments consider the correct biological context.

1. Uniquely Biological Considerations

1. Uniquely Biological Considerations

Before I attempt to propose a structure-function model, there are some legitimate concerns many have made in the literature that I wish to recap in the context of cellular structures. Three of these in particular are relevant to this discussion and I list them below.

1.1 Design for Growth

Engineers are familiar with “design for manufacturing” where design considers not just the final product but also aspects of its manufacturing, which often place constraints on said design. Nature’s “manufacturing” method involves (at the global level of structure), highly complex growth – these natural growth mechanisms have no parallel in most manufacturing processes. Take for example the flower stalk in Fig 1, which is from a Yucca tree that I found in a parking lot in Arizona.

At first glance, this looks like a good example of overlapping surfaces, one of the 6 categories of cellular structures I covered before. But when you pause for a moment and query the function of this packing of cells (WHY this shape, size, packing?), you realize there is a powerful growth motive for this design. A few weeks later when I returned to the parking lot, I found many of the Yucca stems simultaneously in various stages of bloom – and captured them in a collage shown in Fig 2. This is a staggering level of structural complexity, including integration with the environment (sunlight, temperature, pollinators) that is both wondrous and for an engineer, very humbling.

At first glance, this looks like a good example of overlapping surfaces, one of the 6 categories of cellular structures I covered before. But when you pause for a moment and query the function of this packing of cells (WHY this shape, size, packing?), you realize there is a powerful growth motive for this design. A few weeks later when I returned to the parking lot, I found many of the Yucca stems simultaneously in various stages of bloom – and captured them in a collage shown in Fig 2. This is a staggering level of structural complexity, including integration with the environment (sunlight, temperature, pollinators) that is both wondrous and for an engineer, very humbling.

The lesson here is to recognize growth as a strong driver in every natural structure – the tricky part is determining when the design is constrained by growth as the primary force and when can growth be treated as incidental to achieving an optimum functional objective.

1.2 Multi-functionality

Even setting aside the growth driver mentioned previously, structure in nature is often serving multiple functions at once – and this is true of cellular structures as well. Consider the tessellation of “scutes” on the alligator. If you were tasked with designing armor for a structure, you may be tempted to mimic the alligator skin as shown in Fig. 3.

As you begin to study the skin, you see it is comprised of multiple scutes that have varying shape, size and cross-sections – see Fig 4 for a close-up.

As you begin to study the skin, you see it is comprised of multiple scutes that have varying shape, size and cross-sections – see Fig 4 for a close-up.

The pattern varies spatially, but you notice some trends: there exists a pattern on the top but it is different from the sides and the bottom (not pictured here). The only way to make sense of this variation is to ask what functions do these scutes serve? Luckily for us, biologists have given this a great deal of thought and it turns out there are several: bio-protection, thermoregulation, fluid loss mitigation and unrestricted mobility are some of the functions discussed in the literature [1, 2]. So whereas you were initially concerned only with protection (armor), the alligator seeks to accomplish much more – this means the designer either needs to de-confound the various functional aspects spatially and/or expand the search to other examples of natural armor to develop a common principle that emerges independent of multi-functionality specific to each species.

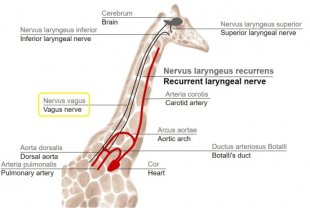

1.3 Sub-Optimal Design

This is an aspect for which I have not found an example in the field of cellular structures (yet), so I will borrow a well-known (and somewhat controversial) example [3] to make this point, and that has to do with the giraffe’s Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve (RLN), which connects the Vagus Nerve to the larynx as shown in Figure 5, which it is argued, takes an unnecessarily long circuitous route to connect these two points.